Jeff Simon

LOCAL POET DISPLAYS A GREATNESS CULTIVATED IN PRIVATE

Published on October 17, 2004

Author: Jeff Simon - ARTS AND BOOKS EDITOR

© The Buffalo News Inc.

Preview

Irving Feldman On the occasion of the publication of his "Collected Poems" (Pantheon/Schocken, 439 pages, $28.50) the MacArthur Prize poet reads from his work at 8 p.m. Wednesday, 250 Baird Hall on the UB North Campus.

Irving Feldman, at 76, is one of the great living American poets.

If you told him so, he'd be startled and pleased but not entirely shocked. This, after all, is a man who, if asked who are the living and dead writers to whom he feels a kinship answers, with some apology, "Shakespeare."

The residence in Buffalo of such a poet since 1964 would, no doubt, shock an entire city. Of the writers' names to drift from the university campus all the way to the city, his is down the list. The late Leslie Fiedler would come first. A Pulitzer Prize might help Carl Dennis come second. Because of his extraordinary literary influence, recent University at Buffalo departee Robert Creeley might come third (or even outdistance Dennis for second).

But Irving Feldman -- despite a MacArthur "genius" grant and five decades of poetry (the last four of them at UB) -- would come far down the list. And that is entirely in his character. A deeply private man -- some might even say reclusive -- he is, by temperament, inimical to the baser operations of celebrity and reputation-building. Even to faculty colleagues and UB students, he is often thought to be austere, forbidding, waspish and something less than back-slapping and gregarious.

He is, in an interview in his West Side apartment, recklessly, sometimes ruthlessly, candid and funny. If there is a puffed-up colleague's reputation to puncture, he will do so with his high gravelly voice and a sweet ingratiating smile. If there is a slicing aphorism to be quoted -- or newly minted on the spot -- he will do so with startling ease. And if there is pleasure to be had applying a precisely aimed laser to American politics and culture, he won't let political correctness or timidity stop him. (About his readers' frequent bafflement at his relative lack of general reputation, he says shruggingly, "I think sometimes it's because people in the poetry world are not grown-up enough. I think they could be president. . . . I was thinking the other day, instead of saving him, maybe Jesus could have just made him grow up.")

He seems, then, not the slightest bit uncomfortable contemplating scorched earth in every direction -- especially if the napalm employed has been his. And that's because he also knows where the verdant glades and oases are.

What is about to happen to Irving Feldman is a dramatic life moment impossible to ignore (or, in his case, to hide from). His "Collected Poems 1954-2004" (Pantheon/Schocken, 437 pages, $27.50) will be published Tuesday, and on the very next day, at 8 p.m., he will give a rare reading of his work in Room 250 of Baird Hall on the UB North Campus.

It is an astonishing collection, different not in degree from his work encountered in contemporary anthologies (which it often is) but in kind. Over the course of 400 pages, one encounters a poet intense, visionary, apocalyptic, wickedly satiric and accomplished on all scales -- small, medium and large. As odd as it seems to say so, he seems to share some of the spiky individualism and independence of a painter like Clyfford Still or a composer like Charles Ives -- not exactly standard equipment for a man born "with a funny Jewish name" (in his words) on Coney Island, educated at City College of New York and Columbia and employed, for his entire life, teaching poetry and literature at a teeming state university.

His youth in New York couldn't have been spent more in the world of New York bohemia. He roomed, for nine months, with James Baldwin and Mason Hoffenberg, co-author with Terry Southern of "Candy." He knew Robert DeNiro Sr. -- the painter -- and has fond memories of junior long before he grew up to be one of the great film actors. ("I knew the actor as a tyke. I used to tie his shoelaces for him. He was also a student of mine at Greenwich house -- as a 4-year-old." Painters, he says slyly, "throw better parties" than literary folk.)

What you have to understand about Feldman is that, for all his perceived austerity, he also listens to sports-talk radio ("It's a terrible confession, but I like to see mankind at its worst") and has pictures of his son and two grandchildren proudly displayed on the refrigerator in his spartan West Side apartment.

A few observations, aphorisms, apercus, and words to remember from a major poet almost certainly about to enjoy the reception of his writing life:

On living in Buffalo and whether he might have been a different poet elsewhere.

"I've always quoted Bachelard 'the provinces are rich in reverie because they are rich in boredom.' (Laughs) . . . What I've half wondered -- and half wished -- is what would have happened had I stayed on in New York and hung around the theater. That would have made for a much different kind of poetry I think. Because the theater is full of making everything fall together at the moment of the performance and JUST for that. So there's less of a mind-set of making things for longer duration, of making the poems live beyond the present.

"And also I think poets are corrupted by their isolation. They can't tell when they're being bores. In the theater, you know right away. The audience goes dead, and then they walk out. The essential thing is the transaction with the audience.

"(In New York's literary world, though) I wouldn't really have participated in a remarkably ungenerous way. I'd rather not take if it means having to give under false pretenses."

On whether or not "Collected Poems" entails intimations of mortality he'd rather not think about.

"It certainly does have that sort of downside to it -- the collected work gets dwarfed in the face of eternity. I wasn't looking to make a summa as such. I just wanted to get my work out again in front of people -- in the hope that people would see all of these together and somehow they might begin to understand any individual poem in terms of the whole body. . .

"Everything I do I have to work at. It has to be homemade. I don't begin on anyone's shoulders. I have to reinvent the giant I'm going to stand on for myself. For (his collection) 'Lost Originals,' for my own purposes, I reinvented romanticism."

On honors, awards and such.

"Awards are really given by donors for their own sakes so they can believe that they live in a time not wholly devoid of talent. A poet's real audience is only six or seven or eight or nine intimate friends, for whom he writes -- and, of course, the dead, for whom they also write. Any audience larger than that, any wholesale audience, is meaningless.

"(Nevertheless, a 400-page "Collected Poems" exists because) you feel a certain responsibility to the work. It's there. You made it. You want people to know it."

On the marked difference between what Feldman experienced piecemeal in anthologies and wholesale in a "Collected Poems."

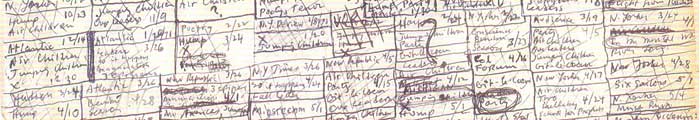

"It's usually just the Jewish poems that are printed in anthologies. . . . What it leads you to do is understand how anthologies are made. They're made essentially by lazy people who want to reprint stuff that's already been in anthologies. They're going to sell the anthologies to schools, pretty much. They know that teachers want to teach poems they've already taught."

Of his most famous and much-anthologized colleagues over the years in the UB English Department.

"(Charles) Olson was a lot different from (Robert) Creeley -- a very expansive type and inclusive. . . . He felt he belonged in the pantheon. And therefore he didn't want to dismiss anyone else from the pantheon. William Carlos Williams could stay in it -- had to stay in it. It made it a bigger pantheon. He was an expansive guy. I can't say as much for Creeley, who bought into -- and propagated, although he's mellowed now -- what I call 'the black legend of William Carlos Williams,' which Williams was into himself, this bitterness at having been shunned by the establishment, whatever that is. I always felt, 'Well, if he had the pleasure of writing those poems, what more do you need?'

"(Departed poet Charles) Bernstein I could observe in action building his empire from the word 'go.' I knew even before he came he was power hungry. I always wonder about people like that -- what kind of interior emptiness they're trying to fill with power. His poetry shows a certain kind of interior emptiness, I think."

On the differences he has noticed in students over the years.

"Something happened in 1970 to all of the students. After Kent State, the wind went out of them. The students I used to see back then were much more engaged in a literary way than most of the ones I've seen since. . . . (Before Kent State) Since young people don't have any power of any kind, the only power they have is the power of the word. That means renaming things. That's what Charles Olson gave them. It was very exciting. . .

"What strikes me now is a kind of complacency. They really seem not to want to know anything beyond what they themselves have just done. I don't know whether that's the point of the kind of generational divides that have been created by marketing. When I grew up, all ages intermingled. We hadn't been separated into marketing niches for the convenience of advertisers. They're terribly self-complacent. Not much interested in the world -- particularly the undergraduates. It's hard to gauge their intellectual capacity, because their minds are not open at all."

On those with a dire view of the prospects for poetry and serious literature of all sorts.

"It's not so bad that it can't get worse. You know Gresham's Law, that the bad money drives the good money out. My addendum to that is always, 'Wouldn't it be nice if it were always very bad money that drove the good money out?' There's a lot of overwhelming mediocrity.

"But I think there's too much literature in general in people's lives. I've long thought that -- too much newspaper stuff, too much media stuff, advertising. We're bombarded by literature all the time which sort of devalues it. I think that probably explains the fixed attention spans people have for what comes along. So that to adapt -- what Benjamin says about original works losing their 'aura' when they're reproduced -- also they lose their aura when they're knocked around all the time.

"If every six months, a storyteller would come by your farm and tell you a new story, how it would glow."

As does, say, a "Collected Poems," finally, by one of America's great living poets.

Poems

In the Eye of the Needle

Up on chairs as if they were floating

toward the kitchen ceiling, two sisters

are having hems set to the season's height,

to the middle of the knee, and no higher,

though they beg for half an inch, a quarter.

Robust and red-haired, they are two angels

beaming and grinning so they could never blow

the marvelous clarions their cheeks imply

-- and I, fang still tender, venom milky,

small serpent smitten, witless with pleasure,

idling, moving my length along, spying,

summoned to Paradise by giggling

and chatter.

I saw this all

in the needle's eye -- before time put it out--

compressed to two girls' gazes, hazel-eyed

and blue-eyed, one gentle, one imperious,

the soul at focus in its instant of sight,

expressive, shining there, revealed;

the seed of light flew down, a spark, two bits

of human seeing, and lay upon my heap

of gazes, bliss inexhaustibly blazing.

The Celebrities

Not themselves, but like photographs of themselves;

and their faces, whether puffy, sleek, or wrinkled,

are faces we cannot imagine anyone

gazed at with love ever -- because they are angels

burned to fierce neutrality by the billion stares

that make them immortal: great, impoverished beings

sprung whole from the eyes of strangers.

The Brother

This great man, this fine public figure,

is stealing his portion, gobbling it up

-- brazenly, in front of everyone's eyes.

And his swagger and blarney and light fingers

and swell-headed pleasure in who he is

have got them all applauding him for that.

And because he gets them to be brazen, too,

they love him for this, calling out to him,

"Fine for you, man. Now let us see you take more!"

But brother (and how his face suffers the face

that likeness nails to it), brother, he gazes

in silence into his empty bowl, and he knows.

e-mail: jsimon@buffnews.com

Photos by Elizabeth A. Mundschenk/Buffalo News

Poet Irving Feldman doesn't let political correctness or timidity stop

him in his critiques of American culture.

Irving Feldman roomed with James Baldwin and knew Robert DeNiro Sr.

while living in New York City.